Intro To AI Hardware For Investors: GPUs Won. That’s Why Everyone Is Hedging Them

GPUs, CPUs, RAM, Silicon, ARM explained. Plus: Margins, and the quiet shift in AI hardware

An investor’s lens on AI hardware

Most AI investment narratives start in the wrong place. They focus on models, benchmarks, and headline-grabbing chip launches, as if the main question is who has the fastest technology. That’s rarely where long-term outcomes are decided.

For investors, AI hardware matters for a simpler reason: it’s becoming one of the largest and least flexible cost lines in modern tech businesses. Compute, memory, power, and supply constraints don’t scale like software, and once AI usage moves from experimentation to production, those constraints start showing up directly in margins, pricing power, and strategic optionality.

This is where a lot of confusion creeps in. Terms like GPUs, ARM, and “custom silicon” get thrown around as if they’re competing bets on the same axis, when in reality they sit at very different layers of the system and serve very different economic purposes. Some choices buy flexibility, others buy efficiency, and a few quietly buy leverage.

This article isn’t about predicting which chip wins or which company ships the fastest accelerator. It’s about understanding how AI hardware actually behaves once it’s embedded into real products at scale, who controls the economics when that happens, and why many of the most important moves in this space are defensive rather than disruptive.

What AI hardware actually is

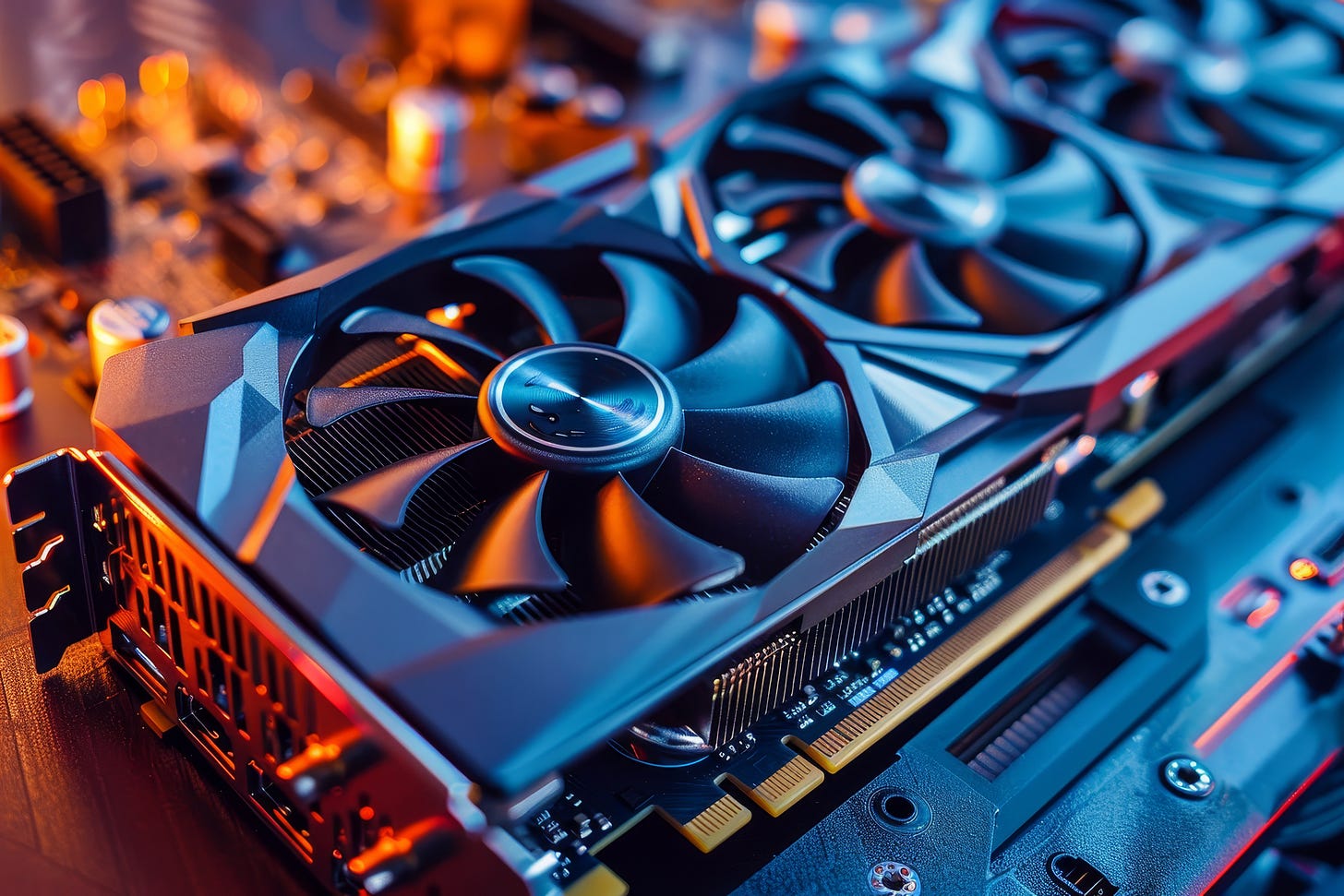

When people talk about AI hardware, they are almost always talking about GPUs, even if they don’t explicitly say it, and that’s already a bit misleading because GPUs were never built for AI in the first place. They were built for graphics, games, video rendering, and other visual workloads, but it turns out that the kind of math you need to draw millions of pixels on a screen looks very similar to the math modern neural networks rely on.

At a high level, AI models are doing massive amounts of repetitive math, mostly matrix multiplications, nothing conceptually complicated, just a huge volume of it. That’s where GPUs happen to shine, because instead of being optimized to do a few complex tasks very quickly, they are built to do the same simple operation thousands of times in parallel.

This is the key difference compared to CPUs. A CPU is great at decision-making, branching, and juggling many different tasks at once, which is why it’s perfect for running an operating system. A GPU is more like an assembly line, where every worker repeats the same motion over and over again, which sounds limiting until you realize that this is exactly what AI workloads want.

How GPUs quietly became the backbone of AI

No one sat down and designed a “perfect AI chip” at the beginning. Researchers simply used the hardware that was already available and eventually realized that GPUs could run neural network workloads much faster than CPUs, which triggered a chain reaction that still shapes the industry today.

Once AI frameworks started targeting GPUs, model architectures adapted to GPU behavior, tooling improved, and developers learned to think in GPU-friendly ways. Over time, the GPU stopped being an optimization choice and became an assumption, something everything else was built around rather than something you consciously evaluated.

That’s why GPUs didn’t win because they were theoretically ideal. They won because they were good enough early on and then accumulated an ecosystem so large that replacing them became a tooling, cultural, and economic problem, not just a technical one.

About training and inference

From the outside, all AI compute looks roughly the same, but once you’re paying for it the difference between training and inference becomes very obvious. Training is expensive and painful, but it usually happens in bursts, while inference runs continuously in the background and scales directly with how successful your product becomes.

Every chatbot reply, every generated image, every recommendation is inference, and once users expect those features to work instantly and all the time, you don’t get to pause or batch that workload later. This is where hardware flexibility starts to matter more than peak efficiency.

GPUs ended up in a sweet spot because they can handle both training and inference reasonably well, even as models and workloads keep changing, and that adaptability turns out to be more valuable in practice than squeezing out a bit more theoretical performance.

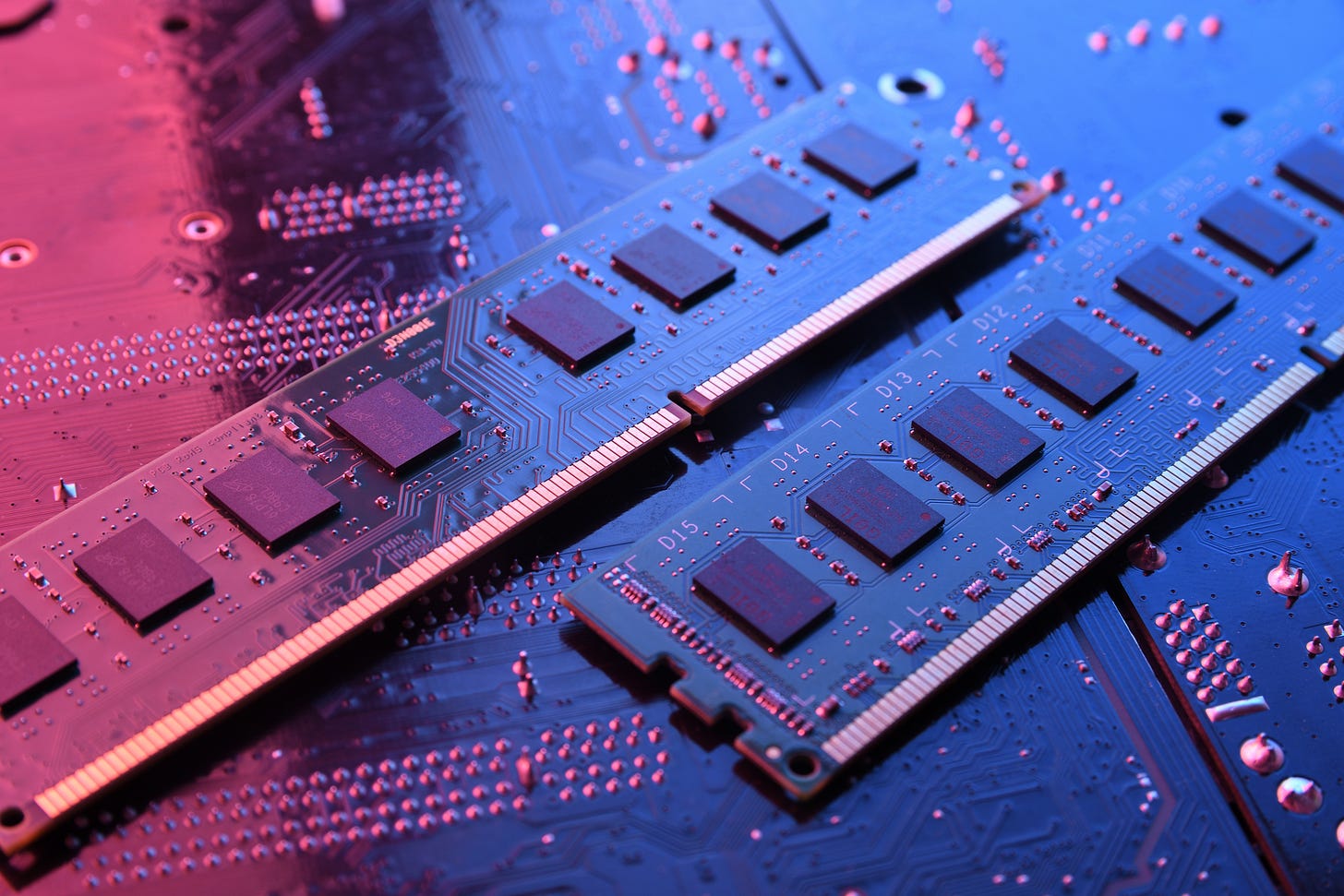

Memory: the part that quietly dominates everything

If GPUs are the muscle of AI systems, memory is the thing that actually keeps them alive, and this is the part many non-hardware people underestimate. AI models are physically large, not just conceptually complex, because all of those parameters have to live somewhere and be moved around constantly while the model runs.

If that movement is slow, the GPU ends up waiting, and a GPU that’s waiting is still drawing power, still occupying rack space, and still showing up on the bill. In many real-world systems, the bottleneck isn’t how fast the GPU can calculate but how fast it can get data.

That’s why memory decisions matter just as much as compute decisions, even though they usually get far less attention.

System RAM and GPU memory

There’s system RAM, which sits next to the CPU and is relatively cheap and flexible, and then there’s GPU memory, often called VRAM or high-bandwidth memory, which is much faster, much closer to the GPU cores, and dramatically more expensive per gigabyte.

AI workloads strongly prefer to keep the entire model inside GPU memory. The moment parts of it spill into system RAM, performance drops sharply, latency increases, and power usage creeps up in ways that don’t show up in benchmarks but absolutely show up in cloud invoices.

This is why AI GPUs are expensive. You’re not just paying for compute, you’re paying for fast, scarce memory that’s tightly coupled to that compute, and once you hit memory limits you can’t fix the problem cheaply without changing the whole performance profile of the system.

Memory bandwidth: the quiet limiter

In practice, many AI workloads are memory-bound rather than compute-bound, meaning the GPU could theoretically do more work but spends a lot of time waiting for data to arrive. That unused capacity is still paid for in electricity and capital, which is why it becomes an economic problem, not just a technical one.

This also explains why newer generations of GPUs focus so heavily on memory bandwidth and interconnects. Faster memory leads to higher real utilization, which lowers cost per request and often matters more than raw compute improvements.

From the outside, this looks like a minor spec detail. From the inside, it’s one of the main drivers of margins.

Why memory makes AI infrastructure sticky

Once an AI system is built around a certain memory setup, it tends to stick, because models get tuned to specific sizes, engineers optimize around bandwidth assumptions, and lots of small, invisible decisions accumulate over time.

Switching hardware later is rarely a clean swap. It usually means retuning models, rewriting performance-critical code, and accepting new edge cases and failure modes, which is why hardware choices in AI tend to last longer than software choices and why GPUs, with their tightly integrated compute and memory, became so deeply entrenched.

This stickiness is also what makes any serious attempt to replace GPUs much harder than it looks at first glance.

With GPUs and Memory covered, I want to talk about CPUs next, which in the AI space is often erroneously referred to “silicon”.

What “silicon” actually means in AI conversations

When people say “silicon” in AI discussions, they’re usually not talking about a specific kind of chip at all. It’s shorthand for hardware a company designs itself instead of buying off the shelf. Almost every modern processor is made of silicon, whether it’s a CPU, a GPU, or an AI accelerator, so the material isn’t the point. What matters is who controls the design and what assumptions are baked into it.

When you hear phrases like “Apple’s silicon” or “custom silicon for AI,” what’s really being described is a decision to take ownership over part of the hardware stack rather than accept someone else’s roadmap, pricing, and constraints. Therefore silicon isn’t a category of hardware.

I often hear ARM as equally misunderstood term in discussions, so let’s tackle that next:

ARM is not a chip, it’s the language CPUs speak

ARM is often described as a chip company, but that’s slightly misleading. ARM mostly doesn’t build chips. It defines an instruction set, essentially the language a CPU speaks. That language specifies how software talks to hardware, how instructions are structured, and how memory is accessed. ARM became popular because it’s efficient, modular, and easy to license, which is why it dominates phones and is now spreading into laptops and servers.

When companies design ARM-based chips, they aren’t inventing CPUs from scratch. They’re starting from a shared language and building their own cores, memory systems, and accelerators around it. ARM answers one specific question: how the CPU part of a chip behaves. That’s important, but it’s not where most AI computation happens.

CPUs still matter, just not for the heavy AI lifting

CPUs, whether ARM-based or not, are still essential. They run the operating system, handle networking, schedule workloads, and keep the system stable. What they don’t do well is the massive parallel math modern AI models rely on, which is why GPUs took over training and large-scale inference.

When people talk about “ARM for AI,” they usually mean ARM CPUs coordinating AI workloads, not replacing GPUs. The CPU is the conductor, not the orchestra.

Custom AI chips are purpose-built accelerators

Custom AI chips live in a different category altogether. These are purpose-built accelerators designed to run neural networks efficiently under specific assumptions. They support a narrower set of operations, trade flexibility for efficiency, and are usually aimed at inference workloads where models are stable and traffic is predictable.

They don’t replace CPUs or GPUs. They sit alongside them and handle the parts of the system where efficiency matters more than adaptability.

How these pieces fit together in real systems

In real AI systems, these components stack rather than compete. A CPU handles orchestration and system logic, a GPU handles flexible high-performance compute, and a custom accelerator handles narrow, high-volume inference paths.

Once you look at the system this way, the current hardware strategies become much easier to understand. Companies aren’t choosing between ARM, GPUs, or custom chips. They’re deciding which layers of the stack they want to control directly and which ones they’re willing to rent.

Why all of this quietly pushes companies toward custom silicon

Once you really sit with how tightly compute and memory are tied together in modern AI systems, a lot of current hardware decisions start to look less mysterious. GPUs didn’t just win because they were fast, they won because they bundled compute, memory, software tooling, and developer habits into one package that’s extremely hard to unwind without breaking things in subtle, expensive ways.

That stickiness is great when you’re building on top of it and terrible once you’re dependent on it.

At small scale, none of this feels dramatic. You spin up instances, pay the bill, and focus on shipping product. But as usage grows, inference runs constantly, memory inefficiencies start showing up in real money, and suddenly hardware stops being an abstract infrastructure layer and starts shaping what you can and can’t afford to do.

At that point, GPUs stop being “just the best option” and start becoming a structural dependency. Pricing is set somewhere else. Supply constraints are out of your control. Hardware roadmaps begin to leak into product roadmaps in ways software teams usually don’t like to admit.

This is where the conversation shifts, not toward replacing GPUs outright, because that’s far harder than it sounds, but toward asking a quieter question: how much of this dependency are we actually comfortable with over the long term?

That’s where custom silicon shows up.

The mistake is to think custom chips are about building something fundamentally better than GPUs. Most of the time they aren’t. They’re about creating an escape hatch, even if it’s narrow, limited to certain workloads, or only economically sensible at very large scale.

Once a company can say that not every workload needs to run on GPUs, the balance of power changes a bit. Pricing discussions look different. Shortages hurt less; if you’re into gaming or AI infrastructure you surely know what I’m talking about. Roadmaps become something you negotiate around instead of something you simply accept.

In that sense, custom silicon isn’t a revolution or a bold bet on a new future. It’s what happens when GPUs and memory become important enough that relying on a single external supplier starts to feel risky.

This isn’t theoretical. Big tech is already acting this way.

Once you look at AI hardware through the lens of dependency and leverage, the current moves by big tech stop looking experimental and start looking inevitable. None of the major players are behaving as if the GPU era is about to end, but none of them are behaving as if full dependency on a single hardware supplier is acceptable either.

They’re all converging on the same strategy from different angles: keep GPUs central, but reduce how much power any one supplier has over the system as a whole.

Apple: control the stack or don’t play the game

Apple is often held up as the example of how custom silicon can be transformative, and that’s true, but it’s also why Apple is such a bad comparison for almost everyone else.

Apple didn’t build its own chips because GPUs were too expensive or because it wanted better benchmarks. In my opinion, it built them because Apple hates being dependent on anyone else’s roadmap. Performance per watt, battery life, thermals, form factor, software APIs, developer tooling, all of that becomes much easier to reason about once the silicon is yours.

What’s interesting is how directly this thinking maps to AI, even though Apple’s AI story looks very different from cloud providers. Running more inference on-device only makes sense if you control compute and memory tightly, because latency, power usage, and privacy constraints all collapse into hardware decisions.

Apple’s takeaway isn’t “custom silicon beats GPUs.”

It’s “control compounds when you own the whole system.”

Microsoft: hedge the dependency, don’t fight it

Microsoft sits in a very different position. It doesn’t control consumer hardware at scale, but it does run one of the largest cloud platforms in the world, and that makes GPU dependency a balance sheet problem rather than a technical curiosity.

Azure’s AI push is deeply GPU-centric, and Microsoft is one of the biggest customers NVIDIA will ever have. At the same time, Microsoft is very clearly investing in its own silicon, not because it believes it can replace GPUs overnight, but because relying exclusively on someone else’s pricing, supply, and roadmap is a long-term risk.

Exactly, this is the hedge in its purest form.

Some workloads stay on GPUs because flexibility matters. Others slowly move to internal accelerators where performance is predictable and margins matter more than raw capability. The goal isn’t technical dominance, but it’s optionality.

Microsoft doesn’t need custom silicon to win. It needs it so that GPUs don’t get to set all the rules.

NVIDIA: leaning into dominance without pretending it’s forever

What makes NVIDIA interesting is that it’s not behaving like a company that thinks this dependency will never be challenged. NVIDIA knows better than anyone how fragile dominance can be in hardware.

Instead of just selling chips, NVIDIA keeps expanding the surface area of what “a GPU” even means. Software stacks, networking, interconnects, developer tooling, and increasingly entire data center reference architectures. The goal is to make the GPU not just a component but the default way AI systems are built.

At the same time, NVIDIA is pushing aggressively into higher memory bandwidth, tighter integration, and system-level solutions, which is exactly what you’d expect if you understand that memory and utilization, not just compute, are where the real leverage lives.

NVIDIA isn’t ignoring custom silicon. It’s pricing, bundling, and integrating in a way that makes leaving as expensive and risky as possible.

Different strategies, same direction

Apple, Microsoft, and NVIDIA are doing very different things on the surface, but underneath, the incentives line up neatly.

Apple wants total control, because it can afford to build everything itself.

Microsoft wants leverage and margin protection at massive scale.

NVIDIA wants to remain unavoidable, even as customers hedge against it.

None of these companies are betting on a clean break from GPUs. None of them are acting like custom silicon is a silver bullet. They’re all behaving as if AI hardware is now core infrastructure, closer to energy or networking than to normal software, and infrastructure rewards control, redundancy, and leverage.

Custom silicon isn’t showing up because GPUs failed, but it’s showing up because GPUs succeeded so completely that depending on them alone became risky.

From here, the remaining question isn’t whether custom silicon “wins,” but how much dependency reduction is enough before the complexity stops being worth it.

Closing thoughts

If you strip away the hype, the benchmarks, and the chip launch headlines, what’s happening in AI hardware is actually pretty familiar for the development of new systems in tech. Systems that start out flexible and cheap eventually become critical infrastructure, and once that happens, the conversation shifts from performance to control, cost, and risk.

GPUs didn’t become central to AI because they were perfect. They became central because they were available, flexible, and good enough early on, and then everything else quietly aligned around them. Memory, tooling, developer habits, pricing models, and product expectations all piled on top until walking away stopped being a technical decision and started being an economic one.

Custom silicon is a reaction to that. Not as a rebellion against GPUs, and not because everyone suddenly discovered a better way to do math, but because depending entirely on someone else’s hardware, memory roadmap, and pricing power feels fine at small scale and dangerous at large scale. The bigger the AI footprint gets, the more that risk matters.

That’s why the most interesting signal right now isn’t who claims to have the fastest chip, but who is quietly building options.

From an investing perspective, this is where a lot of narratives break. Custom silicon doesn’t automatically mean disruption, and GPU dominance doesn’t automatically mean permanent pricing power. What matters is who controls enough of the stack to survive margin pressure (see my other articles), supply shocks, and the slow grind of inference costs over time.

AI hardware is starting to look less like software and more like utilities. Boring, expensive, politically constrained, and incredibly hard to unwind once you’re in too deep (except if you read and subscribe to my Substack of course).

I hope this article could give you a good overview of hardware involved in AI and you’ll understand hardware news better now. Don’t forget to like and share this article. If you have any questions or comments, don’t hesitate to post them.

Update: If you want to learn more about a specific custom silicon from Google called TPU, I got you covered:

Thanks again for your comments everyone, I've included Nebius and NVIDIA in my latest article about TPUs: https://techfundamentals.substack.com/p/why-google-built-tpus-and-why-investors

What will this dependence on Nvidia mean for nebius?